10 films that shone for their editing and montage through the decades

1920s: The Man with the Camera (Chelovek s kino-apparatom, directed by Dziga Vertov and edited by Yelizaveta Svílova, 1929). The culminating work of a true pioneer of montage, characterized by a breakneck pace that explored resources never seen (or used like this) until then: jump cuts, continuity, freeze frames, upside-down footage, stop-motion, fast and slow motion or split screens. Soviet avant-garde cinema that opened up new forms of expression and has been strongly reclaimed in recent years.

1930s: The Triumph of the Will (Triumph des Willens, directed and edited by Leni Riefenstahl, 1935). The great National Socialist propaganda film with 60 hours filmed during the 1934 Nuremberg Congress condensed into less than 2 hours during a 5-month editing process. Intended to look documentary-like, Riefenstahl used all the means at her disposal (sets created by Albert Speer, cameras, extras, among others) and introduced them with vibrant editing that starts with the tracking shot of Hitler's plane landing in Nuremberg. It continues to mark the way we view Nazism and the depiction of evil in cinema.

1940s: Citizen Kane (Citizen Kane, directed by Orson Welles, edited by Robert Wise, 1941). If it is considered one of the best films in history, it is largely thanks to its innovative narrative discourse created with montage. The use of flashback to tell the story, the clash of space-time in the same sequence and scenes such as the narration of Kane's first marriage through 16 years of breakfasts or his life through newspapers (created from 127 different clips) made it the beginning of a new era for Hollywood full of narrative possibilities.

1950s: The Seven Samurai (Shichinin no samurai, directed and edited by Akira Kurosawa, 1954). The battle sequences, like the end of the film, demonstrate Kurosawa's absolute mastery of editing: agility, combination of speed and pauses, aesthetic taste and narrative capacity with which the viewer is able to understand everything that happens. One of Kurosawa's secrets is that, after a day of shooting, he was able to edit all the filmed material and capture all that energy in his work.

1960s: Bonnie and Clyde (Bonnie and Clyde, directed by Arthur Penn and edited by Dede Allen, 1967). In a decade marked by masterpieces of editing, Bonnie and Clyde stands out for its use of contrast: the contrast of shots and scenes manage to create contrasting atmospheres, with moments for humor or romance but always with tension lurking. The final scene is a cinema classic thanks to the use of cameras rolling at different speeds, mixed in the editing room to lead to the fatal destiny of the protagonists.

1970s: The Godfather (The Godfather, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, edited by William Reynolds and Peter Zinner, 1972). One of the secrets of the first film about the Corleone family is its editing, capable of running calmly but with thrilling moments, reflecting the Family's search for balance through violence. There are no abrupt cuts between scenes, but rather transitions in which images are superimposed, allowing the viewer to breathe. The highlight of the film and its montage is the baptism: two scenes happening at the same time intersect, juxtaposing Michael's renunciation of Satan at the same time as the Family executes his orders.

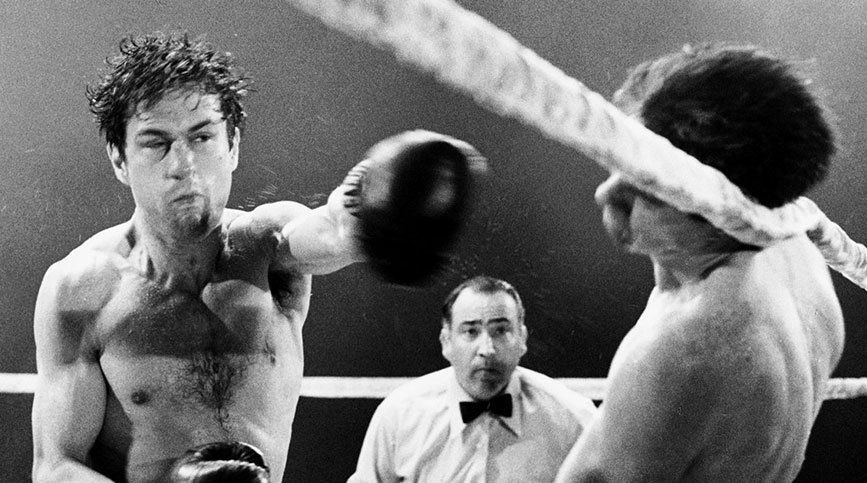

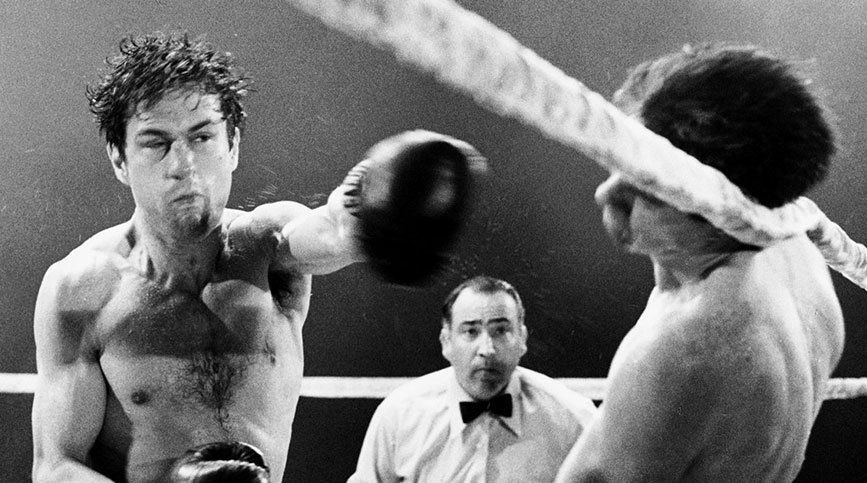

1980s: Raging Bull (Raging Bull, directed by Martin Scorsese and edited by Thelma Schoonmaker, 1980). The film enters the narrative as if it were a documentary about boxing, with pioneering subjective cameras that use different speeds and combine different shots: closed to see all that the blows imply, open to understand the fight, tilted angles or 360º. Most surprisingly, the eight fights last only 10 minutes out of 129 total, but they permeate the entire tone of the film.

1990s: JFK: Cold Case (JFK, directed by Oliver Stone, edited by Joe Hutshing and Pietro Scalia, 1991). This documentary thriller about the assassination of John F. Kennedy won the Oscar for best editing thanks to its innovative techniques: quick cuts and a combination of very diverse footage, from real television news to recreations, photographs, different formats and the use of models. The result is a magnificent puzzle with the climax at the trial, which ends with a call to the viewer to question the possible conspiracies surrounding Lee Harvey Oswald.

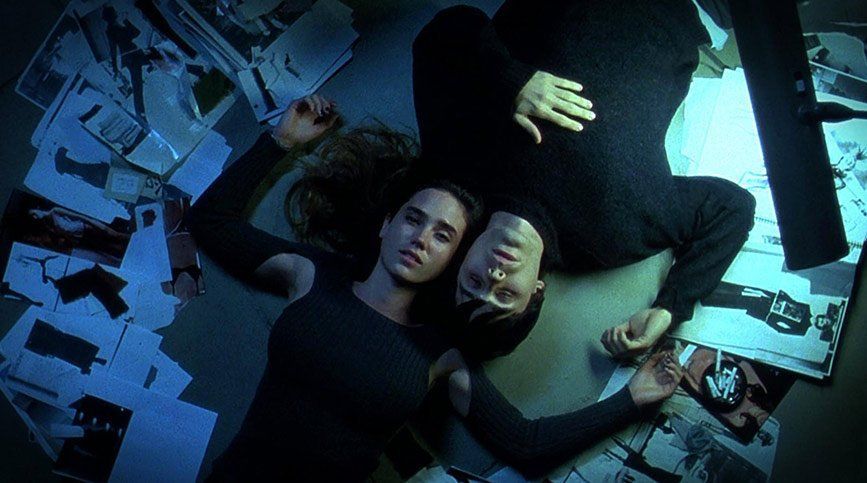

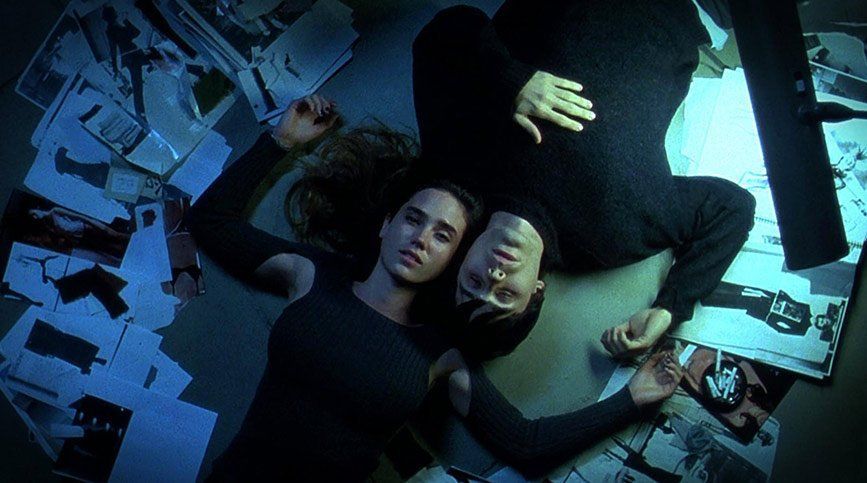

2000s: Requiem for a Dream (Requiem for a Dream, directed by Darren Aronofsky, edited by Jay Rabinowitz, 2000). This anti-drug plea manages, through its vibrant editing (more than 2000 cuts, as opposed to the usual 600 in cinema), to convey to the viewer all the emotions of its protagonists. His original editing, fast and inventive jump-cuts (immediate time jumps without changing scenery or shot) was called hip-hop montage. Aronofsky also took advantage of split-screen resources, very close shot cuts or distortions to create one of the most influential works of the last two decades.

2010s: Inception (Inception, directed by Christopher Nolan, edited by Lee Smith). One of the most surprising and innovative film edits thanks to its non-linear chronology, elegant single cuts and use of parallel editing, techniques Nolan already explored in Memento (absent from this list but should be noted). All the complexity of the story's multiple dreamlike layers find meaning for the viewer through masterful editing, able to mix fast-paced scenes with slow motion without being jerky and to tidy up a film that might have been incomprehensible without the work in the editing room.

As you have seen throughout these 10 films, editing and editing is a crucial phase for any audiovisual project. It is a creative process capable of leading a film to be considered a masterpiece.

If you want to specialize in this field and demonstrate your talent and creativity, on March 4 begins the Professional Master in Audiovisual Editing and Editing. Follow the link for more information and contact us: the course starts in a few days!